SEARCH FOR EVIDENCE (GCP - HTA)

This chapter describes the methods of a literature review for the KCE. It provides guidance for reviewers on the various steps of the search, appraisal and presentation of the results.

New evidence may change some of the recommendations made, thereby researchers should consider this as a ‘living document’ for which yearly updates will be required.

This document is mainly based on the following sources of information:

- KCE Process Documents and Notes (KCE and Deloitte, 2003)

- The Cochrane Collaboration Handbook (Higgins and Green, 2011)

- SIGN 50 (SIGN, 2008)

- CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD), 2009)

- The QUOROM statement (Moher et al., 1999)

- GRADE (Grade org)

- The KCE Process Notes GCP (Van den Bruel et al., 2007), HSR (Van de Voorde and Léonard, 2007), HTA (Cleemput et al., 2007).

An evidence report consists of the following steps:

1. Introduction

A protocol for carrying out a review is equivalent to, and as important as, a protocol for a primary research study. A review is less likely to be biased if the questions are well developed beforehand, and the methods that will be used to answer them are decided on before gathering the necessary data and drawing inferences. In the absence of a protocol, it is possible that study selection and analysis will be unduly driven by (a presumption of) the findings.

A search strategy consists of several aspects. The research question (in a structured format, see Building a search question) should be used as a guide to direct the search strategy. For electronic searches, it is important to list the databases in which studies will be sought. Other sources can be consulted in order to identify all relevant studies. These include reference lists from relevant primary and review articles, journals, grey literature and conference proceedings, research registers, researchers and manufacturers, and the internet.

In practice, it is uncommon for a single search to cover all the questions being addressed within a review. Different questions may be best answered by different databases, or may rely on different study types. Authors are encouraged to take an iterative approach to the search, carrying out a search for high-level evidence first. After evaluating the results of this first search, the questions may need to be redefined and subsequent searches may need to be focused on more appropriate sources and study types.

In some cases, directly relevant good-quality evidence syntheses (secondary sources), such as good-quality systematic reviews or Health Technology Assessments (HTA), will be available on some of the issues that fall within the remit of the review. In these circumstances reference will be made to the existing evidence rather than repeating work that already has been done. All HTA reports or systematic reviews that are identified must be evaluated on their quality and must be shown to have followed an acceptable methodology before they can be considered for use in this way.

In other cases existing evidence may not be directly relevant or may be found to have methodological weaknesses. In these cases, existing evidence cannot be used in the review. Nevertheless, excluded systematic reviews or HTA reports still can be a useful source of references that might be used later on in the review.

In conclusion, literature searches for the KCE should follow an iterative approach, searching for evidence syntheses first and subsequently complementing this search by searching for original studies. Various resources are listed in the following paragraph.

2. Building a search question

Constructing an effective combination of search terms for searching electronic databases requires a structured approach. One approach involves breaking down the review question into ‘facets’. Several generic templates exist, e.g. PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome and Study design), PIRT (Population, Index test, Reference test, Target disorder), SPICE, ECLIPSE, SPIDER, etc. (See Appendices).

The next stage is to identify the search terms in each ‘facet’ which best capture the subject. The group of search terms covering each facet of the review question should include a range of text words (free text to be searched in the title or abstract of studies). Text words and their variants can be identified by reading relevant reviews and primary studies identified during earlier searches or a pre-assessment of the literature. Information on the subject indexing used by databases can be found by consulting the relevant indexing manuals and by noting the manner in which key retrieved articles have been indexed by a given database.

The final search strategy will be developed by an iterative process in which groups of terms are used, perhaps in several permutations, to identify the combination of terms that seems most sensitive in identifying relevant studies. This requires skilled adaptation of search strategies based on knowledge of the subject area, the subject headings and the combination of ‘facets’ which best capture the topic.

3. Searching electronic sources

The decision on which source to use depends on the research question. The three electronic bibliographic databases generally considered being the richest sources of primary studies - MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CENTRAL - are essential in any literature review for the KCE. However, many other electronic bibliographic databases exist.

Systematic reviews can be found in the Cochrane Database for Systematic Reviews, in DARE or in Medline. Search strategies have been developed to enhance the identification of these types of publications (Kastner, 2009; Montori, 2005).

HTA reports can be found in the HTA database of INAHTA or at individual agencies’ sites (see HTAi vortal under "HTA Agencies and Networks").

Specifically for drugs and technology reviews, data from the US Federal Drug Administration (FDA) or EMA can be helpful.

Providing an exhaustive list of all potential sources is not possible here. The KCE library catalogue provides a list of such sources.

Access to electronic resources happens through the following digital libraries:

More than 10.000 e-journals and 8700 Ebooks (IP recognition)

More than 10.000 e-journals and 8700 Ebooks (IP recognition)

Access to databases, journals and eBooks via CEBAM DLH (login required)

Access to databases, journals and eBooks via CEBAM DLH (login required)

3.1 Sources of biomedical literature

Core databases

- MEDLINE contains records from 5600 journals (39 languages) in the of biomedical field, from 1946 onwards (Access for KCE | Free access through PubMed).

- EMBASE: Records from 7600 journals (70 countries, 2000 not covered by Medline) in biomedical field, from 1974 onwards (Access for KCE).

- CENTRAL - The Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, part of the Cochrane Library: Records of randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials in healthcare identified through the work of the Cochrane Collaboration including large numbers of records from MEDLINE and EMBASE as well as much material not covered by these databases (Dickersin, 2002). (Access for KCE through CDLH | Free access to abstracts)

Databases for systematic reviews

- CRD Database of reviews of effectiveness (DARE) contains structured abstracts, including critical appraisal, of systematic reviews identified by regular searching of bibliographic databases, and handsearching of key journals. [the update of CRD DARE has ceased March 2015]

- Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR, part of the Cochrane Library) lists the results of systematic reviews (full text) conducted by Cochrane groups, but also ongoing projects (Access for KCE through CDLH | Free access to abstracts)

- Special queries exist for Medline or Embase to limit the identified records to articles identified as Systematic reviews. See appendix.

Databases for HTA reports

- The INAHTA HTA database is a bibliographical database of published HTA reports; it also lists ongoing HTA projects. Members of INAHTA are regularly invited to update their information on the HTA database, informaiton from the main HTA producers is also collected by the database maintainer. Access is free, records of the HTA database are also searchable via the Cochrane Library.

- HTA reports can also be found at individual agencies’ sites, the HTAi vortal lists HTA organisations, it also provides a custom Web search engine that limits the Google results to pages published on the website of HTA organisations listed on the HTAi vortal.

Databases for specific topics

- Nursing: CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), British Nursing Index (BNI) (Access for KCE through CDLH)

- Physiotherapy: PEDro (contains records of RCTs, systematic reviews and evidence-based clinical practice guidelines in physiotherapy, from 1929 onwards; most trials in the database have been rated for quality to quickly discriminate between trials that are likely to be valid and interpretable and those that are not; free access)

- Psychology and Psychiatry: PsycInfo (Access for KCE)

- More bibliographic databases are listed on the KCE library catalogue (e.g. CAM, ageing, ...)

3.2 Sources of economic literature

Core database

- NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) contains over 7000 abstracts of quality assessed economic evaluations. The database aims to assist decision-makers by systematically identifying and describing economic evaluations, appraising their quality and highlighting their relative strengths and weaknesses. [the update of CRD NHS EED has ceased March 2015]

- Some of the search filters for Medline or Embase limit the records to articles related to Costs, Economic evaluations, Economics

Complementary databases

- EconLit:database of economics publications including peer-reviewed journal articles, working papers from leading universities, PhD dissertations, books, collective volume articles, conference proceedings, and book reviews (Access for KCE)

3.3 Sources of clinical practice guidelines

Often, specific guidelines can only be retrieved through local websites of scientific associations or government agencies. It is therefore recommended to combine a Medline search (with specific filters for guidelines) with a search of the following:

- National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC): a US-based database of clinical practice guidelines primarily in the English language; free access

- International Guideline Library (G-I-N): database of the Guideline International Network (KCE is member of GIN and has full access to the records)

- EBMpracticenet: DUODECIM guidelines, free access in Belgium, funded by RIZIV-INAMI, translation in Dutch and French; adaptation to Belgian context ongoing

- More sources of guidelines are available on BIBKCE under Databases, Practice Guidelines or Practice Guideline, Publishers' catalogue

3.4 Sources of ongoing clinical trials

Ongoing trials may have limited use as a means of identifying studies relevant to systematic reviews, but may be important so that when a review is later updated, these studies can be assessed for possible inclusion. Several initiatives have been taken recently to register ongoing trials:

- International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP)

- EU Clinical Trials Register

- ClinicalTrials.gov

- Current Controlled Trials

- More clinical trials register are listed on the KCE library catalogue

3.5. Sources of grey literature

More and more electronic sources describe "grey literature" (results of scientific research not published in scientific journals; e.g. reports, working papers, thesis, conference papers, ...)

Institutional repositories

- OAIster

- Base

- OpenAIRE

- EconPapers (REPEC)

- More repositories are listed on the KCE library catalogue

3.6 Building a search strategy

For each database, search terms defined in the preparation phase will be mapped to the Thesaurus terms of the database (when available). Mapping can be achieved using the built-in functionality of the search interface, or manually by looking at the indexation of previously identified pertinent articles. Attention will need to be paid to the explosion tool (sometimes selected by default linke in PubMed, sometimes not like in OVID Medline).

The most important synonyms of the Thesaurus terms identified for each facet will also be added to the search strategy as text word. Advanced functionalities of the search interfaces will be used (see below: truncation, wildcard, proximity operators).

The terms within a specific facet will be combined with the Boolean operator ‘OR’ in order to group all articles dealing with this facet. For some concepts, special queries (also called search filters) have been developed (see below). The resulting groups of articles will then be combined using the Boolean operator ‘AND’.

It is recommended to validate each search strategy by a second reviewer.

3.6.1 Search tools

Boolean and proximity operators

In the context of database searching, Boolean logic refers to the logical relationships among search terms. Classical Boolean operators are ‘AND’, ‘OR’ and ‘NOT’, which can be used in most databases. Importantly, in some databases, such as PubMed, these Booleans need to be entered in uppercase letters. Other operators, the so-called proximity operators, are ‘NEAR’, ‘NEXT’ and ‘ADJ’. A more detailed overview of Boolean and proximity operators is provided in Appendix.

Truncation & wildcards

Truncation can be used when all terms that begin with a given text string are to be found. Different databases use different characters for truncation with different functionalities. For example, in PubMed, OVID and EMBASE ‘unlimited’ truncation is represented by the asterix ‘*’, but OVID Medline also uses ‘$’.

In OVID Medline the ‘optional’ wildcard character ‘?’ can be used within or at the end of a search term to substitute for 1 or 0 characters. In contrast, in EMBASE a question mark indicates exactly one character.

A more detailed overview is provided in appendix.

3.6.2 Search limits

When the amount of resulting hits is too high to be managed within the available timeframe / resources, search limits may be applied.

First, tools related to the Thesaurus should be considered:

- Focus / Major Heading: limits to the articles that have been indexed with the term as Major Heading. This helps to reduce the amount of results (up to 40%) while keeping a good pertinence thanks to the human indexation of the full article (in case of Medline and Embase).

- Subheading: these are also added to the description of an article by the indexers, but should be used with more precaution (can render the search strategy too restrictive).

Several search interfaces provide search limits that can also be applied to narrow the search. Classical examples are date and language limits, but some databases also provide limits according to age, gender, publication type etc. Before applying search limits, the risk of a too specific (i.e. narrow) search should be considered.

3.6.3. Search filters

In systematic reviews, if time and resources allow, specificity is often sacrificed in favour of sensitivity, to maximize the yield of relevant articles. Therefore, it is not unusual to retrieve large numbers (possibly thousands) of bibliographic references for consideration for inclusion in an extensive systematic review. This means that reviewers may have to spend a lot of time scanning references to identify perhaps a limited number of relevant studies.

Search filters are available to focus the search according to the type of study that is sought, for example to focus on randomized controlled trials, diagnostic accuracy studies, prognostic studies or systematic reviews (see example in appendix). Specific search filters also exist for well-circumscribed clinical problems/populations, e.g. child health (Boluyt, 2008), palliative care (Sladek, 2007), or nephrology (Garg, 2009).

Sources of filters include:

- PubMed at the Clinical Queries screen

- InterTASC: http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/intertasc/index.htm

- SIGN website: http://www.sign.ac.uk/methodology/filters.html

- HiRU: http://hiru.mcmaster.ca/hiru/

- OVID or Embase.com

During the selection of an appropriate search filter, aspects of testing and validation should play an important role. Specific appraisal tools are available to evaluate the methodological quality of search filters (Bak, 2009; Glanville, 2009).

For diagnostic studies, it is recommended not to use a search filter.

3.7 Documenting a search strategy

The search strategy for electronic databases should be described in sufficient detail to allow that

- the process could be replicated

- an explanation could be provided regarding any study not included in the final report (identified by electronic sources search or not)

The template required by KCE to describe a search strategy is provided in attachment.

All identified references must be exported, preferably in a text file to be imported in a Reference Management Software (see appendix for technical description).

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| process_04_template_-_search_strategy_1.doc | 38 KB |

| process_04_template_-_search_strategy_1.odt | 10.76 KB |

4. Searching supplementary sources

Checking references lists

- Authors should check the reference lists of articles obtained (including those from previously published systematic reviews) to identify relevant reports. The process of following up references from one article to another is generally an efficient means of identifying studies for possible inclusion in a review.

- Because investigators may selectively cite studies with positive results (Gotzsche 1987; Ravnskov 1992), reference lists should never be used as a sole approach to identifying reports for a review, but rather as an adjunct to other approaches.

Using related citation tools

- Several electronic sources provide a "Find related" functionality. This functionality is often based on a poorly detailed (and thus difficult to describe and reproduce) algorithm (using theseaurus terms, keywords, ...). Therefore, we recommend to list the identified supplemental references under "Related citations".

- Several electronic sources provide a "find citing articles" functionality. This functionality is often related to the quality of the references provided by the authors and thus not always exact. Therefore, we recommend to list the identified supplemental references under "Citing articles".

Other supplementary sources

- Websites

- Handsearching of journals

- Experts in the field

- Etc.

5. Searching for evidence on adverse effects

The first sources to investigate for information on adverse effects are reports from trials or other studies included in the systematic review. Excluded reports might also provide some useful information.

There are a number of specific sources of information on adverse effects of drugs, including:

- Europe: European Medicines Agency, www.ema.europa.eu

- US: Food and Drug Administration, www.fda.gov/medwatch

- UK: Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, www.mhra.gov.uk

- Australia: Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin, www.tga.gov.au/adr/aadrb.htm

- The Netherlands: Landelijke Registratie en Evaluatie van Bijwerkingen, www.lareb.nl

In Belgium, there is currently no public database on adverse drug events. Regulatory authorities (such as the websites of FDA and EMA) and the drug manufacturer may be able to provide some information. Information on adverse effects should also be sought from other types of studies than those considered appropriate for the systematic review (e.g. cohort and case-control studies, uncontrolled [phase I and II] trials, case series and case reports). However, all such studies and reports are subject to bias to a greater extent than randomized trials, and findings must be interpreted with caution.

6. Selecting studies

Study selection is a multi-stage process. The process by which studies will be selected for inclusion in a review should be described in the review protocol.

6.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The final inclusion/exclusion decisions should be made after retrieving the full texts of all potentially relevant citations. Reviewers should assess the information contained in these reports to see whether the criteria have been met or not. Many of the citations initially included may be excluded at this stage.

The criteria used to select studies for inclusion in the review must be clearly stated:

6.1.1. Types of participants

The diseases or conditions of interest should be described here, including any restrictions on diagnoses, age groups and settings. Subgroup analyses should not be listed here.

6.1.2. Type of interventions

Experimental and control interventions should be defined here, making it clear which comparisons are of interest. Restrictions on dose, frequency, intensity or duration should be stated. Subgroup analyses should not be listed here.

6.1.3. Types of outcome measures

Note that outcome measures do not always form part of the criteria for including studies in a review. If they do not, then this should be made clear. Outcome measures of interest should be listed in this section whether or not they form part of the inclusion criteria.

For most reviews it will be worthwhile to pilot test the inclusion criteria on a sample of articles (say ten to twelve papers, including ones that are thought to be definitely eligible, definitely not eligible and questionable). The pilot test can be used to refine and clarify the inclusion criteria, train the people who will be applying them and ensure that the criteria can be applied consistently by more than one person.

Even when explicit inclusion criteria have been specified, decisions concerning the inclusion of individual studies remain relatively subjective. There is evidence that using at least two authors has an important effect on reducing the possibility that relevant reports will be discarded (Edwards et al. 2002). Agreement between assessors may be formally assessed mathematically using Cohen's Kappa (a measure of chance-corrected agreement). Many disagreements may be simple oversights, whilst others may be matters of interpretation. These disagreements should be discussed, and where possible resolved by consensus after referring to the protocol. If disagreement is due to lack of information, the authors may have to be contacted for clarification. Any disagreements and their resolution should be recorded.

The influence of uncertainty about study selection may be investigated in a sensitivity analysis.

It is useful to construct a list of excluded studies at this point, detailing the reason for each exclusion. This list may be included in the report of the review as an appendix. The final report of the review should also include a flow chart or a table detailing the studies included and excluded from the review. In appendix a flow chart is provided for documenting study selection. If resources and time allow, the lists of included and excluded studies may be discussed with the expert panel. It may be useful to have a mixture of subject experts and methodological experts assessing inclusion.

6.1.4. Types of studies

Eligible study designs should be stated here, along with any thresholds for inclusion based on the conduct or quality of the studies. For example, ‘All randomised controlled comparisons’ or ‘All randomised controlled trials with blind assessment of outcome’. Exclusion of particular types of randomised studies (for example, cross-over trials) should be justified.

It is generally for authors to decide which study design(s) to include in their review. Some reviews are more restrictive, and include only randomized trials, while others are less restrictive, and include other study designs as well, particularly when few randomized trials addressing the topic of the review are identified. For example, many of the reviews from the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care (EPOC) Collaborative Review Group include before-and-after studies and interrupted time series in addition to randomized and quasi-randomized trials.

6.2. Selection process

Before any papers are acquired for evaluation, sifting of the search output is carried out to eliminate irrelevant material.

- Papers that are clearly not relevant to the key questions are eliminated based on their title.

- Abstracts of remaining papers are then examined and any that are clearly not appropriate study designs, or that fail to meet specific methodological criteria, will be also eliminated at this stage.

- All reports of studies that are identified as potentially eligible must then be assessed in full text to see whether they meet the inclusion criteria for the review.

The reproducibility of this process should be tested in the initial stages of the review, and if reproducibility is shown to be poor more explicit criteria may have to be developed to improve it.

Authors must decide whether more than one author will assess the relevance of each report. Whatever the case, the number of people assessing the relevance of each report should be stated in the Methods section of the review. Some authors may decide that assessments of relevance should be made by people who are blind or masked to the journal from which the article comes, the authors, the institution, and the magnitude and direction of the results by editing copies of the articles (Berlin 1997; Berlin, Miles, and Crigliano 1997). However, this takes much time, and may not be warranted given the resources required and the uncertain benefit in terms of protecting against bias (Berlin 1997).

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Process_06_Template_StudiesSelection_20200716.xls | 314 KB |

7. Quality assessment of studies

Critical appraisal of articles is a crucial part of a literature search. It aims at identifying methodological weaknesses and assessing the quality in a coherent way. The methodological assessment is based on a number of key questions that focus on those aspects of the study design that have a significant influence on the validity of the results reported and conclusions drawn. These key questions differ according to the study type, and a range of checklists can be used to bring a degree of consistency to the assessment process. The checklists for systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, cohort studies and case-control studies discussed below were selected during several internal workshops at the KCE. The other checklists (for diagnosis studies for instance) will also be discussed.

The process of critical appraisal consists of an evaluation by two independent reviewers who confront their results and discuss them with a third reviewer in case of disagreement. However, because of feasibility it could be acceptable that one reviewer does the quality appraisal and that a second reviewer checks the other’s work.

If necessary, the authors of the evaluated study should be contacted for additional information.

The results of the critical appraisal should be reported in a transparent way.

7.1. Critical appraisal of systematic reviews

From the several instruments available to assess methodological quality of reviews (1); KCE recommends the use of AMSTAR 2 (2) that takes into account RCT but also non RCT studies.

An alternative is the ROBINS-tool which is more comprehensive for non randomized studies. (3)

References

(1) See among other overviews

- Zeng X, Zhang Y, Kwong JSW, Zhang C, Li S, Sun F, et al. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine. 2015;8(1):2-10.

- Pieper D, Antoine S-L, Morfeld J-C, Mathes T, Eikermann M. Methodological approaches in conducting overviews: current state in HTA agencies. Research Synthesis Methods. 2014;5(3):187-99

(2) Shea Beverley J, Reeves Barnaby C, Wells George, Thuku Micere, Hamel Candyce, Moran Julian et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both BMJ 2017; 358 :j4008

Updates

[Update 20180126] AMSTAR 2 replaces AMSTAR in the toolbox

AMSTAR 2 aims at responding to AMSTAR's criticisms, among others the fact that AMSTAR does not cover non RCT studies.

- Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:10

- Burda BU, Holmer HK, Norris SL. Limitations of A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) and suggestions for improvement. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):58.

[Update] Dutch Cochrane checklist removed from the toolbox

KCE experts initially selected 2 checklists for quality appraisal: AMSTAR and the Dutch Cochrane checklist. However, the Dutch Cochrane tool is not used anymore by its authors and was never formally validated. It has thus been removed from the toolbox.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| KCEProcessbook_Amstar2-checklist.docx | 47.91 KB |

7.2. Critical appraisal of randomized controlled trials for interventions

For the quality appraisal of randomized controlled trials for interventions, the Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias Tool is recommended [1]. This checklist contains hints on how to interpret and score the individual items, and is summarised in the attachement "Cochrane Collaboration's Risk of Bias Tool". It is also extensively explained in chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook (http://www.cochrane-handbook.org/). Each item can be scored with low, unclear or high risk of bias. Importantly, performance bias (blinding) and attrition bias (incomplete outcome data) should be assessed for each critical and important outcome as selected according to GRADE. If insufficient detail is reported of what happened in the study, the judgement will usually be unclear risk of bias.

The recommended level at which to summarize the risk of bias in a study is for an outcome within a study, because some risks of bias may be different for different outcomes. A summary assessment of the risk of bias for an outcome should include all of the entries relevant to that outcome: i.e. both study-level entries, such as allocation sequence concealment, and outcome specific entries, such as blinding.

Some methodological issues, such as the correctness of the statistical analysis, power, etc. are not specifically addressed in this tool, and should be assessed separately.

The scores can be filled in using the template in attachment.

[1] KCE experts initially selected 2 checklists for quality appraisal: the Risk of Bias Tool and the Dutch Cochrane checklist. However, the Dutch Cochrane tool is not used anymore by its authors and was never formally validated.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Cochrane Collaboration's Risk of Bias Tool.doc | 74.5 KB |

| Template Risk of Bias tool.doc | 41.5 KB |

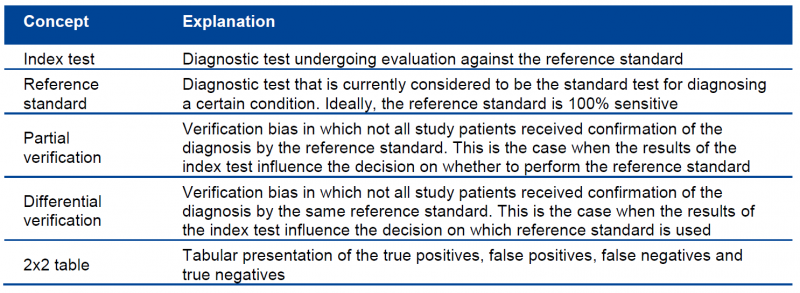

7.3. Critical appraisal of diagnostic accuracy studies

For the quality appraisal of diagnostic accuracy studies, the QUADAS 2 instrument is recommended (Whiting, 2003). The tool is structured so that 4 key domains are each rated in terms of the risk of bias and the concern regarding applicability to the research question. Each key domain has a set of signalling questions to help reach the judgments regarding bias and applicability. A background document on QUADAS 2 can be found on the website: http://www.bris.ac.uk/quadas/quadas-2.

In order to correctly appraise a diagnostic accuracy study, basic knowledge about key concepts is essential. An overview of these concepts is provided in the following table:

Three phases can be distinguished in the QUADAS tool:

- Phase 1: State the review question using the PIRT format (Patients, Index test(s), Reference standard, Target condition)

- Phase 2: Draw a flow diagram for the primary study, showing the process of recruiting, inclusion, exclusion and verification

- Phase 3: Risk of bias and applicability judgments.

The score can be filled in using the template in attachment.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Template QUADAS 2 tool.doc | 59 KB |

7.4. Critical appraisal of observational studies

Unlike systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, diagnostic studies and guidelines, the methodological research community has less agreement on which items to use for the quality appraisal of cohort studies, case-control studies and other types of observational evidence. The Dutch Cochrane Centre has a few checklists available (http://dcc.cochrane.org/beoordelingsformulieren-en-andere-downloads), but these are written in Dutch and were not formally validated. For the evaluation of prospective, non-randomized, controlled trials, the Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias Tool can be used. Other checklists can be found at: http://www.unisa.edu.au/Research/Sansom-Institute-for-Health-Research/Research-at-the-Sansom/Research-Concentrations/Allied-Health-Evidence/Resources/CAT/. GRADE also offers a number of criteria that can be used to judge the methodological quality of observational studies. These are further explained in the chapter on GRADE.

Mainly based on the checklists of SIGN and NICE, the KCE elaborated two new checklists for cohort studies and case-control studies (see attachment).

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Cohort studies_template.docx | 49.9 KB |

| Case-control studies_template.docx | 48.3 KB |

7.5. Critical appraisal of guidelines

For the quality appraisal of clinical practice guidelines, the AGREE II instrument (www.agreetrust.org) is recommended. AGREE II comprises 23 items organized into 6 quality domains: i) scope and purpose; ii) stakeholder involvement; iii) rigour of development; iv) clarity of presentation; v) applicability; and vi) editorial independence. Each of the 23 items targets various aspects of practice guideline quality and can be scored on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Two global rating items allow an overall assessment of the guideline’s quality. Detailed scoring information is provided in the instrument in attachment.

Ideally, the quality appraisal of a guideline is done by 4 reviewers, but because of feasibility 2 reviewers can be considered acceptable.

AGREE II serves 3 purposes:

1. to assess the quality of guidelines;

2. to provide a methodological strategy for the development of guidelines; and

3. to inform what information and how information ought to be reported in guidelines.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| AGREEII.pdf | 392.52 KB |

8. Data extraction

Data extraction implies the process of extracting the information from the selected studies that will be ultimately reported. In order to allow an efficient data extraction, the process should be detailed in the protocol before the literature search is started. Key components of the data extraction include:

- information about study reference(s) and author(s);

- verification of study eligibility;

- study characteristics:

- study methods

- participants

- interventions

- outcomes measures and results

Evidence tables

All validated studies identified from the systematic literature review relating to each key search question are summarized into evidence tables. The content of the evidence tables is determined by the entire project group. Completion for all retained articles is done by one member of the project group and checked by another member. A KCE template for evidence tables was developed using the CoCanCPG evidence tables (www.cocancpg.eu/) and the GIN evidence tables (http://g-i-n.net/activities/etwg/progresses-of-the-etwg) as a basis, and can be found in attachment. A template is available for systematic reviews, intervention studies, diagnostic accuracy studies and prognostic studies.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| evidence tables_final.docx | 66.61 KB |

GRADE evidence profiles

To provide an overview of the body of evidence for each comparison relevant to the research question, GRADE evidence profiles are created and added to the appendix of the report. These evidence profiles can serve as a basis for the content discussions during the expert meetings. To create these evidence profiles it is highly recommended to use the GRADEpro software, which can be downloaded for free (http://ims.cochrane.org/revman/other-resources/gradepro/download).

When a meta-analysis is possible, it is recommended to extract the necessary information to Review Manager (RevMan) first, and subsequently to import this information from RevMan into GRADEpro (using the button ‘Import from RevMan’). More information on the use of RevMan can be found here: http://ims.cochrane.org/revman.

Once all information is extracted in GRADEpro, evidence profiles can be created by clicking the ‘Preview SoF table’ button, selecting the format ‘GRADE evidence profile’ and exporting them to a Word Document.

9. Analysing and interpreting results

Once the eligible studies are selected and quality appraised, the magnitude of the intervention effect should be estimated. The best way to do this is by performing a meta-analysis (i.e. the statistical combination of results from two or more separate studies), although this is not always feasible. An interesting tool for doing a limited meta-analysis is the free Review Manager software of the Cochrane Collaboration.

The starting point of the analysis and interpretation of the study results involves the identification of the data type for the outcome measurements. Five different types of outcome data can be considered:

- dichotomous data: two possible categorical response;

- continuous data

- ordinal data: several ordered categories;

- counts and rates calculated from counting the numbers of events that each individual experiences;

- time-to-event data

Only dichotomous data will be addressed here. Dichotomous outcome data arise when the outcome for every study participant is one of two possibilities, for example, dead or alive. These data can be summarised in a 2x2 table:

| Outcome | |||

| YES | NO | ||

| Intervention | a | b | a + b |

| Control | c | d | c + d |

| a + c | b + d |

The most commonly encountered effect measures used in clinical trials with dichotomous data are:

- Relative risk (RR): the ratio of the risk (i.e. the probability with which the outcome will occur) of the outcome in the two groups, or [a/(a+b)]/[c/(c+d)]. For example, a RR of 3 implies that the outcome with treatment is three times more likely to occur than without treatment;

- Absolute risk reduction (ARR): the absolute difference of the risk of the outcome in the two groups, or [a/(a+b)]-[c/(c+d)];

- Number needed to treat (NNT): the number of persons that need to be treated with the intervention in order to prevent one additional outcome, or 1/ARR.

- For diagnostic accuracy studies, the results will be expressed as

- Sensitivity: the proportion of true positives correctly identified by the test: Sens=a/a+c

- Specificity: the proportion of true negatives correctly identified by the test: Spec=d/b+d

- Positive predictive value: the proportion of patients with a positive test result correctly diagnosed: PPV=a/a+b

- Negative predictive value: the proportion of patients with a negative test result correctly diagnosed: NPV=d/c+d

- Likelihood ratio: likelihood that a given test result would be expected in a patient with the target disorder compared to the likelihood that that same result would be expected in a patient without the target disorder LR+=(a/a+c)/(b/b+d); LR-=(c/a+c)/(d/b+d)

- Diagnostic odds ratio: ratio of the odds of having a positive index test result in a patient with the target condition over the odds of having this test result in a patient without the target condition: OR=ad/bc

| Target condition Positive |

Target condition Negative |

|

| Index test positive | a | b |

| Index test negative | c | d |

As discussed above, other types than dichotomous data are possible, each with their own outcome measures and statistics. It is beyond the scope of this document to describe and discuss all these types. Interested readers are referred to textbooks such as Practical statistics for medical research (Altman 1991) Modern Epidemiology (Rothman and Greenland 1998) and Clinical epidemiology : a basic science for clinical medicine (Sackett 1991) .

10. Reporting of the literature review

A literature search should be reproducible and therefore explicitly documented. The report of a literature search should contain the following items:

1. Description of the search methodology:

a. Search protocol

i. Search question

ii. Searched databases

iii. Search terms, their combinations and the restrictions used (e.g. language, date)

iv. In- and exclusion criteria for the selection of the studies

b. Quality appraisal methodology

c. Data extraction methodology

2. Description of the search results:

a. Number of retrieved articles, in- and excluded studies, and reasons for exclusion; use of flow chart

b. Results of quality appraisal

c. Evidence tables for each search question